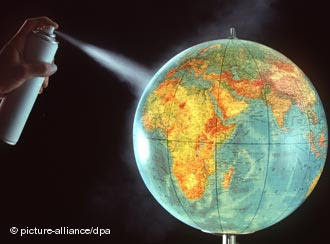

The passage of the Montreal ozone protocol 20 years ago was a milestone in international climate protection. DW-WORLD.DE spoke to Thomas Bunge, a member of the German delegation, who was part of the historic event.

Thomas Bunge represented Germany's Federal Environment Agency in drawing up the "Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer" in September 1987. The lawyer is currently responsible for Environment and Spatial Planning at the agency.

DW-WORLD.DE: Why was the 1987 Montreal protocol so significant?

Thomas Bunge: That was the beginning of international regulations to protect the earth's atmosphere. Until then, there was only regulation of long-range, transnational air pollution. People tried for the first time to resolve a worldwide problem through international law, although in retrospect, the regulations then were certainly inadequate. Can you briefly explain why they were inadequate?

Can you briefly explain why they were inadequate?

The regulations agreed in 1987 were supposed to reduce the production and use of substances that damaged the ozone layer by a maximum of only up to 50 percent. But people very quickly noticed that that wasn't enough to effectively protect the ozone layer. In 1990, that is, a year after the regulations came into effect, the stipulations had already been tightened. The decision was made to entirely discontinue production and use by the year 2000. In 1994, the deadlines were again shortened. Thus people wanted, and still want, to relatively quickly achieve a full discontinuation of production, and also of use, of the substances. It's true that developing countries currently the still have the right to produce and use the substances in small amounts. But relatively soon the use and the production will be discontinued worldwide.

Can you describe how things came about? How is such a compromise reached?

As is normally the case in the realm of international law, there are specific working groups for the individual application areas one aims to regulate. The building blocks for such an international treaty are worked out in the groups. The individual building blocks must then be voted on and approved in the plenum. That is, as in all cases, a compromise between the interests that the individual states represent at these conferences, of course. The whole thing was fleshed out with science and the scientific results available up until the signing in 1987 were included. The interests of the individual states and the scientific results were then put in relation. That led to a compromise with which one was at the time not particularly happy.

Can you provide an example of a practical problem that had to be overcome? Did particular countries block movement?

It was several blocks of states. The European Union comprised its own negotiation block. Of course, that was significantly fewer states than today. There was a so-called "Toronto Group" of states. They represented the Scandinavian states, Canada, Australia and Switzerland. This group with Australia and New Zealand, which would have been affected the soonest by the consequences of the hole in the ozone layer -- and then was affected -- wanted to pass very wide-reaching regulations. On the other side, there was an array of industrial countries that produced these substances. They were naturally interested in continuing production or being able to produce appropriate substitutes.

How was the atmosphere among the conference participants on Sept. 16, 1987, when the protocol was passed?

People were pleased that a compromise had been reached. But we had already seen that the rules weren't sufficient for the next 20, 30, 40 years. We recognized that the progressive states also had had to swallow some bitter pills. But in retrospect, it was a success, of course, to very quickly bring very many countries on board on trade regulations that envisaged limitations on trade with countries that weren't party to the treaty. In this way, one had a model for the negotiations on climate regulations that started relatively soon thereafter.

Found this post useful? Consider subscribing to

Sustainable Affairs Feed/RSS.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario